|

|

|

H-1B Prevailing Wage Claims vs. Reality: |

|||||

|

By Robert Hill, CUNY, Murphy Institute for Worker Education |

|||||

|

Previous Research |

|||||

|

In 2003, after the third consecutive year when the H-1B cap had been raised to 195,000 annually, Professor Norman Matloff published an exhaustive meta-study of previously published research on matters concerning reform of the H-1B program. His 100-page article, published in the University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform, was essentially an argument for significant reforms in the H-1B program to address several glaring problems. The annual caps of 195,000 workers for fiscal years 2001 through 2003 were granted by Congress in large part because the software industry complained aggressively that there were dire shortages of adequately trained domestic software workers. Matloff consulted a wide variety of studies that found that there was indeed no shortage of domestic computer technology labor, but rather an unwillingness of businesses to hire them. In addition to consulting the peer-reviewed literature, though, his study was bolstered by observations of actual data. Figure 2 below is a table taken from Matloff (2003) that demonstrates the extremely low hiring rates by the software industry’s top employers.

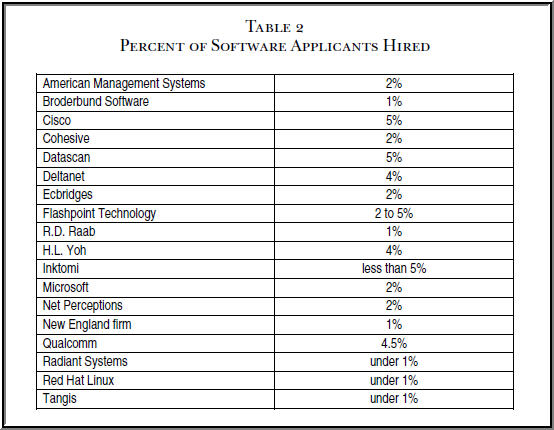

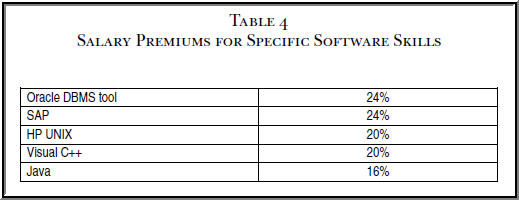

Figure : Table 2 from Matloff (2003) showing extremely low hiring rates. These numbers are percentages of applicants hired. For instance, while Microsoft Chair Bill Gates was repeatedly testifying before Congress that his corporation was unable to find trained domestic workers, his company was actually hiring only about 2% of the people who submitted their resumes for the jobs. Matloff points out that far from being unable to find employees, Microsoft was able to dismiss 98% of the people that sought employment with it. Further, of the 18 top computer technology employers in Matloff’s survey, not one of them hired more than 5% of their applicants. This factual finding was inconsistent with the claim that qualified employees were unavailable. As well, Matloff argues that bringing in an additional 195,000 workers per year would only make these percentages smaller, not larger. The real reason, Matloff argues, that the software industry was seeking ever more H-1B workers is that such workers represent cheap, compliant labor. He cites the Cappelli Principle: workers are available, but not at the price that employers want to pay. The Cappelli Principle is especially relevant to computer technology workers, he argues, because as employers demand highly-specialized skills, accepted market and labor philosophies agree that such skills demand higher wages. Figure 3 below demonstrates the high salary premiums that employers were forced to pay to attract people with these highly-specific skillsets.

Figure 3 : Table 4 from Matloff (2003), showing elevated wages for high-demand skills. Matloff points out that foreign, H-1B workers are not only able to provide these skills, but by increasing the supply of labor employers are relying on the well-accepted market principle that as supply goes up, cost goes down. Thus, the argument is made that the true goal of increasing the supply of H-1B workers is empirically demonstrated to be driven by finances, not supply. In addition to this evidence, Matloff draws from a number of studies documenting the differences between H-1B and domestic wages. Figure 4 below highlights a few comparisons from one of the studies that Matloff surveys.

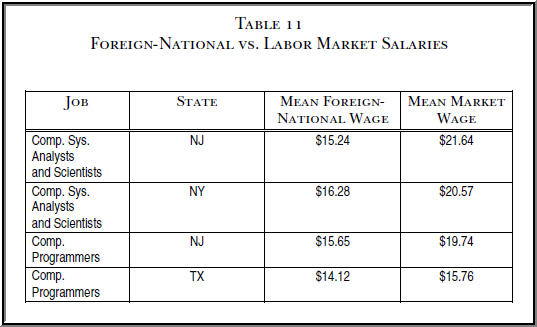

Figure 4 : Table 11 from Matloff (2003), demonstrating typical differences in H-1B vs domestic salaries. In each of the four instances he identifies in his Table 11 (Figure 4 above), mean foreign-national wages were significantly lower than mean market wages for similar work performed in the same work places. Additionally, Matloff identifies two types of savings in labor costs that are consequences employers’ ever-increasing use of H-1B labor. He calls these Type 1 savings and Type 2 savings. Type 1 savings to the employer represent the direct savings accrued by simply paying the H-1B workers less than they would pay domestic workers. For instance, rather than paying a premium of 24% for a domestic Oracle DBMS developer they might be able to pay much less for an H-1B worker with the same skills. Type 2 savings, though, represent another widely suspected financial motivation for employers: the perception that older workers cost more to hire than do younger workers, and that H-1B workers are categorically younger people in addition to being categorically willing to work for lower wages. By favoring H-1B workers whenever possible, employers can increase savings on both salary and age dimensions. Finally, Matloff calls on a variety of governmental and academic studies that indicate that H-1B workers are not only categorically less expensive than domestic workers, they are also much more compliant. “Since an H-1B is typically in no position to seek other employment (due to sponsorship requirements), the employer need not worry that the worker will suddenly leave the employer in the middle of a pressing project. In addition, the employer can force the H-1B to work long hours. To many employers, this “loyalty” aspect is the prime motivation for hiring H-1Bs, whether or not they are saving salary costs in doing so.” Matloff refers to H-1B workers as “de facto indentured servants” because most H-1B workers are hoping to convert their temporary visa status to permanent status via their employer. “This is a multi-year process. Toward the end of the 1990s, the processing time for the two largest H-1B nationalities, Indian and Chinese, was approaching six years. During the time an H-1B’s green card application is being processed, he/she is essentially immobile; switching employers during this time would necessitate starting the green card process all over again, an unthinkable prospect for most.” That is to say, despite the attempted protections against exploitation of the H-1B workers themselves, Matloff argues that most if not virtually all of the “loyalty,” expressed as working 14-hour days for low salaries, is actually a modern form of indentured servitude that translates to economic benefits to employers. For all the strengths of Matloff’s arguments, and in spite of the thoroughness of his 100-page, peer-reviewed journal article, Matloff points out that the inadequate record keeping practices of the LCA and H-1B administrators and employers lead to an inability to determine accurate job titles and prevailing wages. The final part of his article argues for needed reforms. While his list of needed reforms does not call for the adoption of standardized SOC job codes and standardized OES prevailing wage data, he does acknowledge that these record keeping problems make it inherently difficult to accurately assess the available data. In a follow-up effort to determine whether the prevailing wages that were reported on the 2004 and 2005 LCAs was an accurate reflection of the true prevailing wages, Miano (2007) undertook an exhaustive study of the data that was available at that time for FY2005. Miano’s key findings included the following:

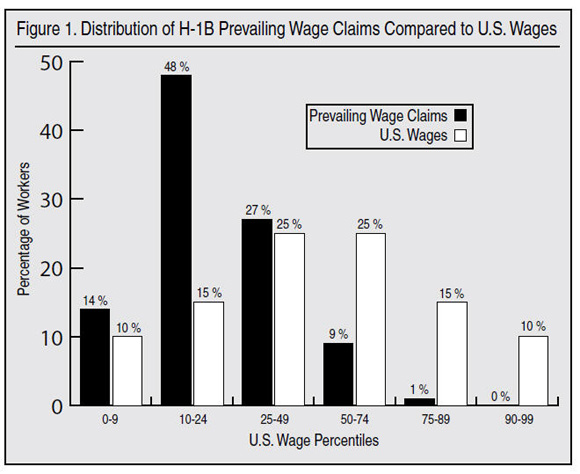

There were several problems that constrained Miano’s research. One is that the data for FY2005 was filed using a combination of two older systems, each of which stored data in differently constructed data structures. The “e-File” system stored one set of information with its naming structure or so-called “schema,” and the “e-FAX” system stored a different set of information using a different schema. Miano included both sources in his calculations, but reported that as the e-FAX system represented a small percentage of the total records it could be disregarded in future research. One of the benefits of the transition to the newer iCert system in April 2009 is that this problem is no longer present for current data: all records are stored in a unified database schema. Another problem that Miano found was that there were various sources of prevailing wages used for the LCAs, and some of them were apparently invalid under the law. For instance, some employers based prevailing wages on surveys provided by private colleges reporting the starting salaries of their graduates. If anything, this data would reflect starting salaries for new graduates, not prevailing wages for experienced domestic workers. And, such data would not necessarily relate to the national or regional prevailing wages, contrary to the requirements set forth in the IMMACT90. While 70% of the LCAs (representing about 50% of the workers) claimed to have used OES data as the basis for the prevailing wages, the FY2005 data was influenced by a change in the law made in 2004. “As discussed, in 2004 Congress added a new prevailing-wage option for employers. It mandated that the Department of Labor provide employers with four skill-based prevailing wages. To comply with this change, the Foreign Labor Certification Data Center took the OES data produced by the Bureau of Labor Statistics and used them to create four skill-based prevailing wages. This created a mechanism for employers to justify low wages. Regardless of the actual skills of an H-1B worker, employers need only assert that a worker is in the Level One category for entry level, trainee, or intern employees, and pay according to that prevailing wage.” Miano calculated that 89% of the H-1B workers were assigned prevailing wages that were below the median prevailing wage for their job code at their location. He deduced, therefore, that the workers were given the prevailing wages for the lower skill and experience levels. Figure 5 below, from Miano (2007), demonstrates this skew graphically.

Figure 5 : Figure 1 from Miano (2007) showing skewed distribution of wages. The two bar charts in Figure 5 refer to prevailing wage claims. The black bars represent the prevailing wages claimed for H-1B workers in FY 2005, and the white bars represent the OES wages for domestic workers in the same field. As the chart demonstrates, both the black distribution and white distribution show a roughly “normal” Bell curve shape. However, the H-1B distribution is heavily skewed to the left, indicating categorically lower prevailing wage claims. Further, 62% (14% plus 48%) of the H-1B prevailing wage claims fell below the 25th percentile rank for domestic workers in similar work categories. The biggest problem that Miano faced was that the LCAs in the FY2005 data used a unique 3-digit occupational code rather than Standard Occupational Classification (SOC) codes. In order to compare the jobs in the LCAs to the Occupational Employment Statistics (OES) data, each LCA had to be associated with the appropriate SOC code. The problem was, the 3-digit codes used by the FY2005 LCAs were much broader than the SOCs. Managers of programmers would be assigned the same 3-digit code as the programmers themselves, making it difficult to compare the prevailing wage claims accurately. Compounding this problem with the data was the fact that job titles were unreliable, insufficiently descriptive, or both. Therefore, Miano faced a huge problem of working to assign LCAs to their appropriate SOC codes so that the data could be reliably compared to the OES data. Problems included instances where the job title was simply “Consultant.” Or, the job titles might reflect “Computer Programmer” but fail to distinguish between an “Application” programmer and “Systems” programmer. OES data are different for those two categories of programmer. Additionally, because of the sheer number of records (over 300,000 LCAs for FY 2005, covering about 700,000 workers – some LCAs are for multiple people), pattern matching techniques were used to try to group similar jobs together. For instance, sorting with a “wildcard” string like “soft*eng*” would return job titles and descriptions that were similar yet not exactly the same. Miano made an effort to discern from the other available data in that LCA, but eventually had to assign some SOC code to every one of them and he acknowledges that this is a weakness in the design of his study.

|

| [Introduction] [History] [LCA / H-1B Process] [For And Against] [Previous Research] [The iCert System] [Methodology (text)] [Methodology (videos)] [Results] [Discussion] [Conclusions] [Downloadable Files] [External Links] |